The app provides templates and backgrounds for videos. (picture information)If you've just opened your own business and need to create...

Aczeno, Porter, Benny Pacheco, Darvin DCO are part of the nine artists who will entertain the afternoon of Wednesday, May...

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) It is the agency responsible for issuing alerts about telluric movements felt throughout North...

These closures are due to a decrease in the number of people using in-person services in branches. Credit: MLambousis |...

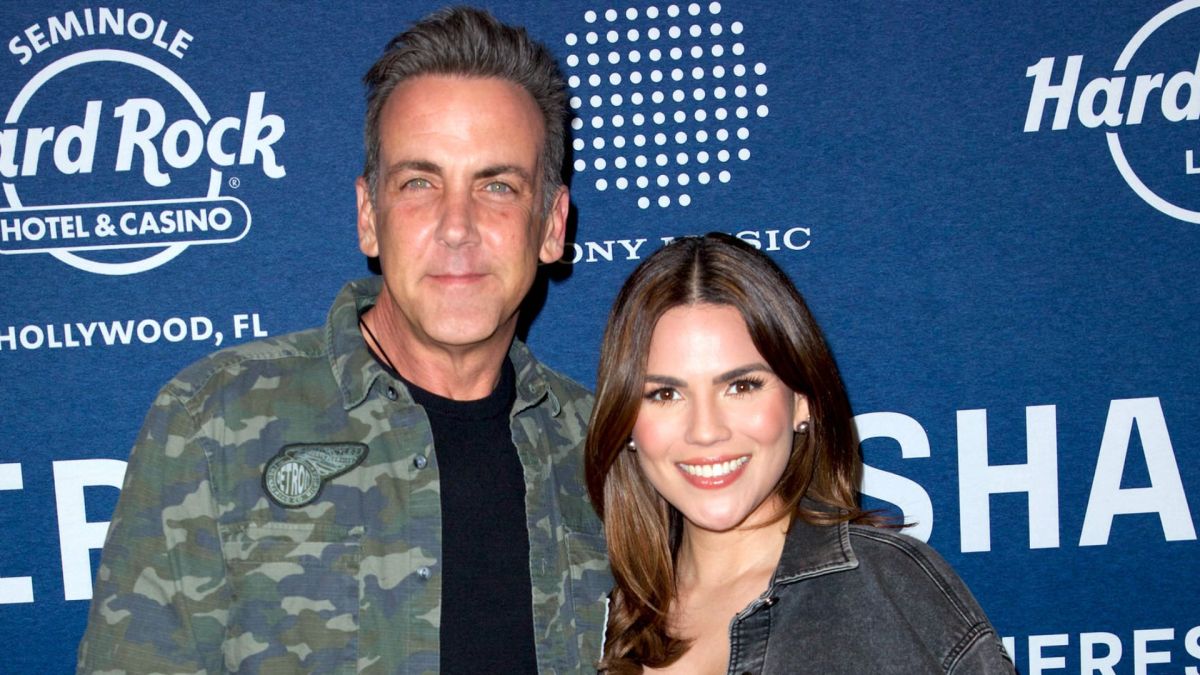

The couple, Karina Banda and Carlos Ponce, are full of long tablecloths due to celebrating their sixth anniversary as a...

Venezuela occupies fourth place at the Ibero-American level, where women lead working groups and research projects in the field of...

May 28, 2024, 11:46 PM ETLed by Anthony Edwards and Karl-Anthony Towns, the Timberwolves were able to contain the Mavericks...

NASA experts They discovered a kind ofMild shock" in it Earth's magnetic field over South America and the South Atlantic...

Morena's presidential candidate and the Ciudadano Movement (MC) candidate will conclude their campaigns in Mexico City on May 29. (Dark...

The options for the President to achieve the dismissal of the Attorney General are reduced. The recent rejection by the...

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/TEQF6EONZRFGLLLDIDD4L2O4EE.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/XU32LRAEZFDDPNVHLFU3CKVBYY.jpg)

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/CITRTMWPUFCOLABRDBESNPJIGQ.jpg)